Division is the operation that shares a total into equal groups or measures how many times one number fits inside another. Students first meet division through stories about sharing snacks fairly or organizing supplies into equal sets. Teachers use counters, cups, and number lines to show that dividing 12 by 3 can mean creating three equal groups or finding groups of three inside 12. This dual meaning—sharing (partitive) and measuring (quotative)—helps students connect division sentences to real contexts. The division symbol, bar, or long division bracket keeps track of the dividend, divisor, and quotient so every step stays organized.

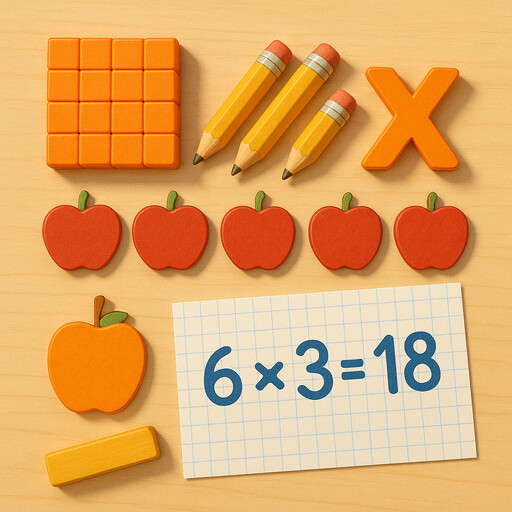

Before formal algorithms, children build understanding with repeated subtraction, arrays, and fact families. They notice that 12 ÷ 3 is the inverse of 3 × 4, so multiplication facts support division facts. Arrays help them see columns and rows splitting apart, while number lines show equal jumps backward. As numbers grow larger, students use place value charts, partial quotients, or area models to partition tens, hundreds, and thousands. These strategies emphasize reasoning about size before following a written procedure.

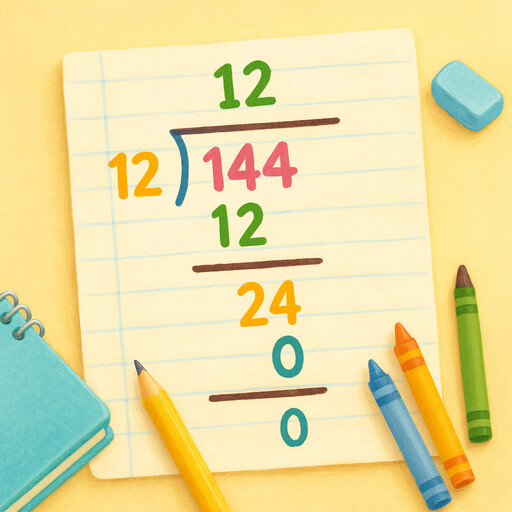

Traditional long division expands on place value thinking. Students ask how many times the divisor fits into each part of the dividend, record the quotient digit, multiply, subtract, and bring down the next digit. This repeated cycle continues until no numbers remain or a remainder appears. When decimals are involved, students place the decimal point directly above in the quotient, then continue dividing by annexing zeros. Teachers encourage estimating before each step to prevent placing a quotient digit that is too large. Checking the result involves multiplying the quotient by the divisor and adding any remainder to see if the dividend returns.

Division appears in recipes, budgeting, travel planning, science experiments, and sports statistics. Chefs divide batter into equal pans, athletes divide distances into laps, and analysts divide totals by time to calculate rates. Understanding division helps students interpret fractions because each fraction represents a division relationship. Estimation strategies like rounding or using compatible numbers make mental division manageable. Technology such as calculators confirms lengthy computations, but clear explanations prove that students own the reasoning.

Effective practice includes games, investigations, and cooperative problem solving. Learners create “divide and conquer” board games, use digital tools that model sharing, or explain division with wordless comics. Teachers highlight unit labels, neat columns, and reflection questions like, “Does this quotient make sense?” Students also explore how division connects to remainders, fractions, and percentages. Mastering division empowers learners to solve rate problems, analyze data, and transition confidently into algebra.

Division

Level

readlittle.com

Sharing and measuring with equal groups

What We Can Learn

- Division can share amounts fairly or measure how many groups fit into a total.

- Models such as arrays, number lines, and partial quotients build understanding before algorithms.

- Long division keeps track of place value through repeated steps of divide, multiply, subtract, and bring down.

- Real-life rates, fractions, and data problems rely on clear division strategies.

Related Reads

Divisibility rule

Shortcuts for spotting factors

Long division

A step-by-step algorithm for multi-digit division

Arithmetic

Everyday math for smart counting

Addition

Joining numbers to make a sum

Subtraction

Finding what remains when amounts change

Multiplication

Combining equal groups efficiently

Fraction

Equal parts of a whole

Decimal

Base-ten numbers with fractional parts