Yellowstone Caldera

readlittle.com

Supervolcano powering geysers and hot springs

Yellowstone Caldera stretches about 55 by 72 kilometers beneath Yellowstone National Park. It formed during three giant eruptions over the past 2.1 million years, the latest occurring 640,000 years ago. The caldera sits atop a mantle plume that melts crust and drives a vast magma reservoir. Surface features include more than 10,000 hydrothermal vents—geysers like Old Faithful, colorful hot springs such as Grand Prismatic Spring, steaming fumaroles, and bubbling mudpots. Travertine terraces at Mammoth Hot Springs grow as hot water deposits dissolved limestone.

While the caldera is often called a "supervolcano," scientists emphasize that catastrophic eruptions are extremely rare. Instead, Yellowstone experiences frequent small earthquakes, hydrothermal explosions, and rhyolitic lava flows (the most recent about 70,000 years ago). The park sits on a rolling cycle of uplift and subsidence as magma and hydrothermal fluids move underground. Modern monitoring includes more than 40 GPS stations, seismometers, gas sensors, and thermal cameras coordinated by the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory (YVO). These instruments stream data to volcanologists who look for patterns that might indicate unrest.

Hydrothermal features provide unique ecosystems. Thermophilic bacteria and archaea thrive in near-boiling pools, creating vivid orange, yellow, and blue rings that vary with water temperature. Scientists study these microbes to understand possible life on other planets and to develop enzymes for industrial applications. However, hydrothermal areas are fragile and can be dangerous; park regulations require visitors to stay on boardwalks because ground crust may be thin and water can exceed 90 °C.

Yellowstone also protects wildlife corridors for bison, elk, grizzly bears, wolves, trumpeter swans, and cutthroat trout. The caldera's geothermal heat influences winter habitats, keeping some valleys relatively snow-free. Indigenous nations, including the Shoshone, Bannock, and Crow peoples, have long histories with the geothermal landscape, using hot springs for cooking, healing, and spiritual practices. Today, 27 associated tribes collaborate with the National Park Service to manage cultural resources and share traditional knowledge with visitors.

Tourism brings millions of people each year to watch Old Faithful erupt, hike the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, and photograph wildlife. Rangers emphasize Leave No Trace principles to protect thermal basins and wildlife. Educational programs let students operate remote cameras, analyze earthquake waveforms, and learn about geothermal energy. Virtual tours and live-streamed geyser eruptions make the caldera's wonders accessible worldwide.

While the caldera is often called a "supervolcano," scientists emphasize that catastrophic eruptions are extremely rare. Instead, Yellowstone experiences frequent small earthquakes, hydrothermal explosions, and rhyolitic lava flows (the most recent about 70,000 years ago). The park sits on a rolling cycle of uplift and subsidence as magma and hydrothermal fluids move underground. Modern monitoring includes more than 40 GPS stations, seismometers, gas sensors, and thermal cameras coordinated by the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory (YVO). These instruments stream data to volcanologists who look for patterns that might indicate unrest.

Hydrothermal features provide unique ecosystems. Thermophilic bacteria and archaea thrive in near-boiling pools, creating vivid orange, yellow, and blue rings that vary with water temperature. Scientists study these microbes to understand possible life on other planets and to develop enzymes for industrial applications. However, hydrothermal areas are fragile and can be dangerous; park regulations require visitors to stay on boardwalks because ground crust may be thin and water can exceed 90 °C.

Yellowstone also protects wildlife corridors for bison, elk, grizzly bears, wolves, trumpeter swans, and cutthroat trout. The caldera's geothermal heat influences winter habitats, keeping some valleys relatively snow-free. Indigenous nations, including the Shoshone, Bannock, and Crow peoples, have long histories with the geothermal landscape, using hot springs for cooking, healing, and spiritual practices. Today, 27 associated tribes collaborate with the National Park Service to manage cultural resources and share traditional knowledge with visitors.

Tourism brings millions of people each year to watch Old Faithful erupt, hike the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, and photograph wildlife. Rangers emphasize Leave No Trace principles to protect thermal basins and wildlife. Educational programs let students operate remote cameras, analyze earthquake waveforms, and learn about geothermal energy. Virtual tours and live-streamed geyser eruptions make the caldera's wonders accessible worldwide.

What We Can Learn

- Yellowstone Caldera formed from multiple massive eruptions and now fuels geysers, hot springs, and mudpots.

- Continuous monitoring by the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory tracks earthquakes, ground deformation, and gas emissions.

- Hydrothermal ecosystems host thermophiles that inspire scientific research.

- Indigenous nations collaborate on stewardship of cultural and natural resources.

- Tourism and education depend on strict safety and conservation practices.

Related Reads

Victoria Falls

The smoke that thunders on the Zambezi

Grand Canyon

Colorado River's layered story

Zhangjiajie National Forest

Sandstone pillar park in Hunan, China

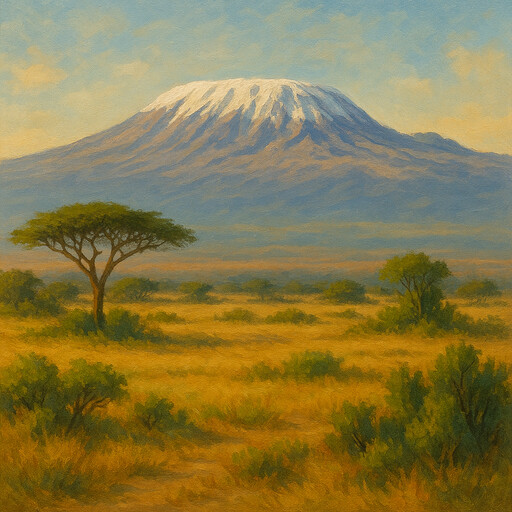

Mount Kilimanjaro

Africa's highest free-standing mountain

Wolf

Pack planners of forests and tundra

Shrew

Tiny insectivores with turbo metabolisms

Bison

Great Plains grazers with thunder hooves

Snake

Silent slitherers with surprising senses

Rabbit

Fast diggers with gentle hearts

Great Barrier Reef

World's largest living coral system

Sahara Desert

Vast sea of sand and stone

Halong Bay

Karst islands in Vietnam's emerald gulf