Bison once numbered in the tens of millions before 19th-century hunting brought them near extinction. Two subspecies remain: the plains bison of the Great Plains and the slightly larger wood bison of northern forests. Adults can weigh over 900 kilograms and stand 1.8 meters tall at the shoulder. Thick brown coats, bearded chins, and curved black horns give them a prehistoric appearance. Their front-heavy build hides a hump formed by elongated vertebrae supporting massive neck muscles that swing heads like snowplows through drifts.

Bison are keystone grazers. They clip grasses close to the ground, stimulating new growth and creating habitat mosaics used by prairie dogs, ground-nesting birds, and pollinators. Their hooves churn soil, pressing seeds into the ground, while dust wallows create bare patches where rare wildflowers sprout. In winter, bison swing their heads side to side to expose buried forage, paving the way for deer and pronghorn that follow in their tracks. Herds may travel dozens of kilometers each week, following seasonal green-up across the plains or between forest meadows and frozen rivers.

Social structure centers on cow-calf groups and bachelor bull bands. In late summer, the rut begins: bulls bellow, display their size, and engage in head-butting contests that send dust clouds into the air. Females give birth to a single reddish calf the following spring after a gestation of about 9.5 months. Calves can stand within an hour and join the herd’s daily marches almost immediately. Bison live up to 20 years in the wild, weathering blizzards by turning their backs to the wind and relying on thick winter coats that shed snow like shingles.

Indigenous nations such as the Lakota, Blackfeet, and Assiniboine developed cultures intertwined with bison, using hides for tipis, bones for tools, and meat for sustenance. The near-eradication of bison disrupted ecosystems and human communities alike. Today, Tribal-led herds, national parks like Yellowstone, and non-profit preserves collaborate to rebuild wild populations while respecting cultural ties. Modern challenges include habitat fragmentation by roads or fences, disease management around cattle, and ensuring genetic diversity as herds expand.

Conservation successes include the transfer of disease-free Yellowstone bison to Tribal lands, the creation of the American Prairie Reserve in Montana, and cooperative grazing agreements with ranchers. Students can analyze satellite imagery to see how grazing shapes vegetation, simulate herd movements with agent-based models, or compare carbon storage in grazed versus ungrazed prairie plots. Learning about bison fosters appreciation for the resilience of grasslands and the people who steward them.

Bison

Level

readlittle.com

Great Plains grazers with thunder hooves

What We Can Learn

- Bison are North America’s largest land mammals and keystone grazers.

- Their movements, wallows, and diets create diverse prairie habitats.

- The rut features roaring bulls, while calves are born each spring after 9.5 months.

- Tribal leadership, parks, and preserves are restoring herds and cultural connections.

Related Reads

Johann Gottfried Herder

German thinker of culture and language

Ming dynasty

Chinese dynasty from 1368 to 1644

Habitat

Natural home of living things

Renaissance

Period of cultural change in Europe

Polynesia

Island region of the Pacific Ocean

Kinship

Family relationships and social ties

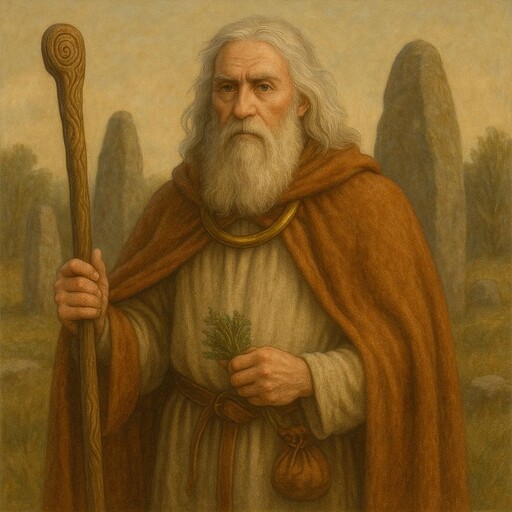

Celts

Ancient peoples of Europe

Scandinavia

Northern region of Europe

Anglo-Saxons

Early peoples of England

Vikings

Seafaring people of northern Europe

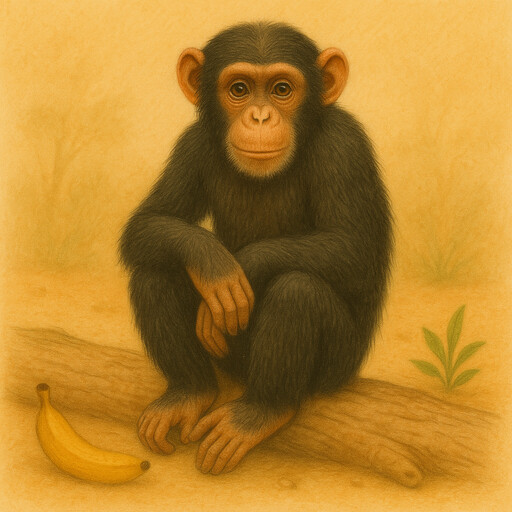

Chimpanzee

Inventive problem-solvers of African forests

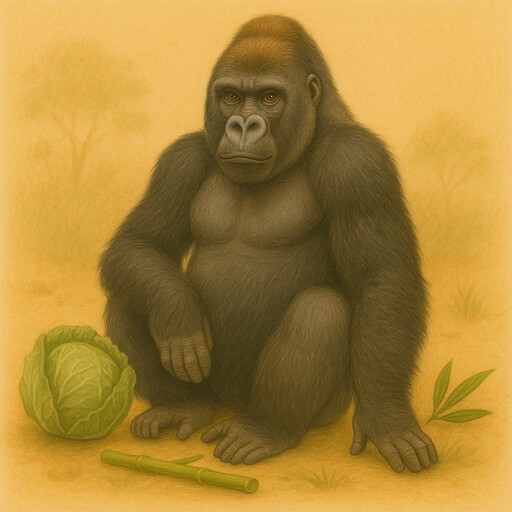

Gorilla

Forest gardeners with gentle strength