Wolf packs once roamed across North America, Europe, and Asia. Though often feared, wolves are shy around humans and focus on natural prey—elk, deer, bison, wild boar, and beaver. Their bodies blend speed and endurance: long legs, narrow chests, and wide paws allow wolves to trot 50 kilometers in a day while gripping icy slopes. Thick double-layered coats insulate against −40 °C windchill, and bushy tails wrap around noses during frigid naps.

Packs typically contain a bonded breeding pair, their offspring from multiple years, and occasionally unrelated adults. Members cooperate like a team. Scouts locate herds, flanking wolves push prey into open areas, and the strongest animals seize the target’s nose or flanks while others anchor hind legs. Hunts do not always succeed, but coordination helps wolves test herds and remove weak individuals, improving overall ecosystem health.

Communication keeps the pack synchronized. Howls broadcast location, rally hunters, and warn rival packs to stay away. Wolves also communicate through body posture, ear position, and scent marks left by urine and raised leg choreographed signals. Pups are born in late spring after a 63-day gestation. Dens carved into riverbanks or hollow logs shelter litters of four to six. Adults rotate babysitting duty, regurgitating chewed meat for pups once they leave the den at three weeks. By autumn, yearlings join hunts and help feed younger siblings the following year.

Human persecution once shrank wolf ranges dramatically through bounties and poisoning. Modern reintroduction efforts, such as the 1995 release in Yellowstone National Park, demonstrate wolves’ ecological role. By reducing over-browsing elk, wolves indirectly allowed willows, aspens, and beavers to rebound, which stabilized riverbanks and provided habitat for birds and fish. Still, wolves sometimes prey on livestock, prompting conflict with ranchers. Non-lethal deterrents—range riders, fladry (flagged fences), guardian dogs, and compensation programs—help reduce retaliatory killing.

Scientists track wolves using GPS collars, snow tracking, and howling surveys. Genetic studies reveal how dispersing wolves maintain diversity by traveling hundreds of kilometers before joining new packs. Students can simulate pack hunts with relay games, map wolf recovery zones, or analyze how prey populations change after wolf return. Learning about wolves encourages nuanced thinking about predators, wilderness, and shared landscapes.

Wolf

Level

readlittle.com

Pack planners of forests and tundra

What We Can Learn

- Wolves live in cooperative family packs that hunt, raise pups, and defend territory together.

- Howls, scent marks, and body language keep pack members organized.

- Wolves influence ecosystems by controlling herbivore numbers and enabling plant recovery.

- Coexistence relies on deterrents, compensation, and respect for both wildlife and rural livelihoods.

Related Reads

Natural selection

How living things change over time

Habitat

Natural home of living things

Smartphone

Mobile phone with advanced computing features

Internet

Global network connecting computers worldwide

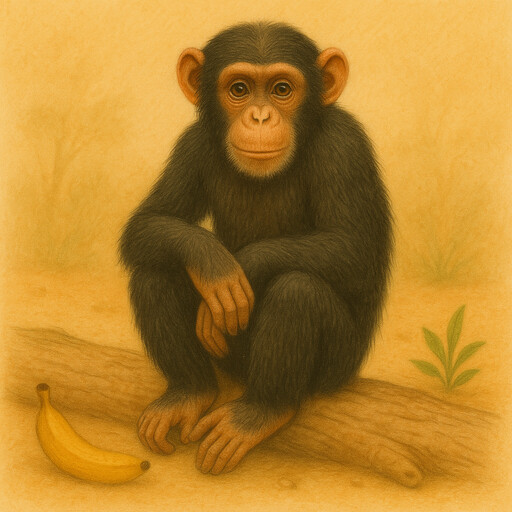

Chimpanzee

Inventive problem-solvers of African forests

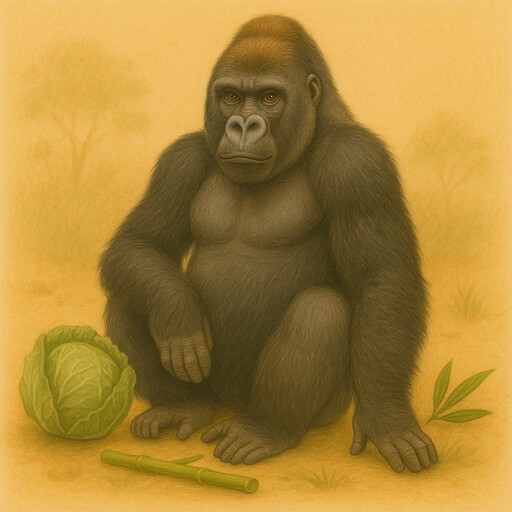

Gorilla

Forest gardeners with gentle strength

Gelada

Grass-eating monkeys of the highlands

Howler monkey

Rainforest alarm bells

Mongoose

Quick hunters with shared dens

Baboon

Savanna troubleshooters

Pygmy marmoset

Thumb-sized sap specialist

Orangutan

Solitary engineers of the canopy