Toad species share a common ancestor with frogs but evolved thicker, bumpier skin and shorter legs suited to life on land. Their warts are harmless glands that exude protective oils, while large parotoid glands behind the eyes secrete milky toxins that deter predators. Toads crawl or take short hops rather than long leaps, conserving energy as they patrol gardens, forests, and even urban yards for beetles, slugs, and ants.

Breeding still requires water. In spring, male toads gather at ponds or roadside ditches, producing high-pitched trills to attract females. Females lay strings of eggs that wrap around vegetation, and tadpoles hatch within days. Because toad skin loses moisture slowly, juveniles disperse farther from water than frogs, hiding under logs or burrowing into loose soil during dry spells. Some desert species dig deep retreats and secrete mucous cocoons to survive months without rain.

Toad diets benefit gardeners by reducing pest populations without pesticides. They swallow prey whole and rely on a sticky tongue that flips out faster than a blink. At night, porch lights attract insects, drawing toads to suburban patios. In turn, snakes, owls, and raccoons prey on toads, though many predators avoid the bitter toxins.

Threats include habitat loss, road mortality during breeding migrations, and invasive species such as cane toads introduced beyond their native range. Conservationists build amphibian tunnels under roads, restore small wetlands, and educate residents about rescuing toads from window wells. Some regions control invasive cane toads to protect native wildlife.

Students can help by constructing toad houses from simple clay pots, recording nightly calls, and monitoring local ponds for egg strings. Science lessons compare frog and toad adaptations or test how moisture levels influence toad activity. By leaving leaf litter in gardens and reducing chemical use, communities invite these warty wanderers to keep ecosystems humming.

Toad

Level

readlittle.com

Warty wanderers that thrive on land

What We Can Learn

- Toads have warty, toxin-secreting skin and short legs adapted to terrestrial life.

- They breed in water but disperse widely on land, eating pests that benefit gardens.

- Threats include habitat loss, roads, and invasive species.

- Amphibian tunnels, backyard shelters, and reduced pesticide use support toad populations.

Related Reads

Natural selection

How living things change over time

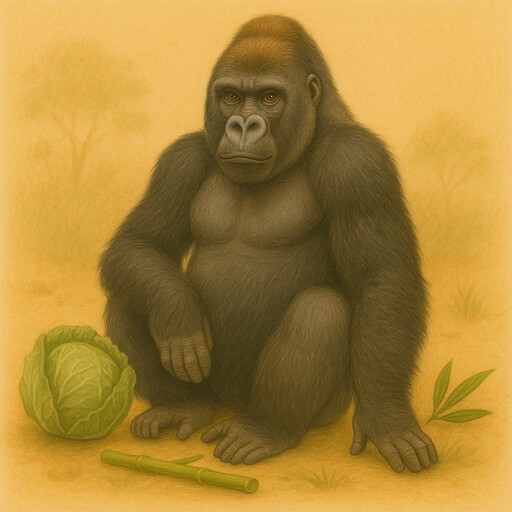

Gorilla

Forest gardeners with gentle strength

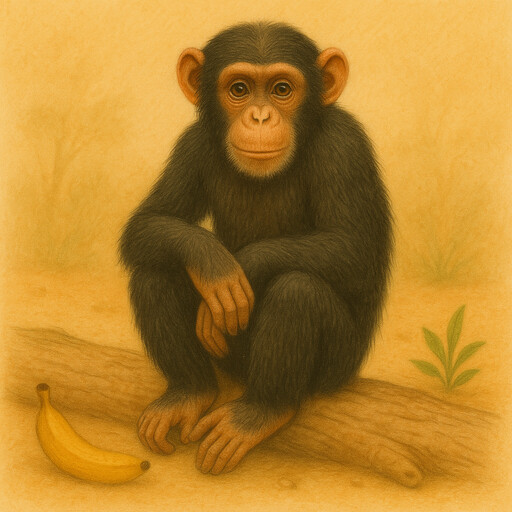

Chimpanzee

Inventive problem-solvers of African forests

Ape

Tailless primates with flexible minds

Orangutan

Solitary engineers of the canopy

Saki

Shaggy-tailed seed eaters

Gelada

Grass-eating monkeys of the highlands

Baboon

Savanna troubleshooters

Tamarin

Tiny monkeys with bold mustaches

Mongoose

Quick hunters with shared dens

Pygmy marmoset

Thumb-sized sap specialist

Howler monkey

Rainforest alarm bells